Benign Neglect Can Be a Good Thing

A significant reason I purchased this particular house is because the abuse it had suffered–and what house of any substantive age has not suffered abuse of one kind or another!–was of the best kind (at least for someone interested in restoration). I call it “benign neglect.”

On the one hand, the previous owners hadn’t done much maintenance work on the house. (So I faced a lot of deferred maintenance projects when I moved in.) On the other hand, they hadn’t done much to mess with its essential integrity either! They didn’t replace plaster walls with drywall, put a kitschy bar in the basement, knock down walls to transform it into an open space design, or any number of other renovations that would have destroyed the original character of the house. Importantly, they didn’t do the most common and devastating “upgrade” that would have destroyed its integrity. They didn’t replace the windows! And they didn’t throw out original doors either!1 (Not only windows, but doors also–these two things contribute more to sustaining architectural integrity than homeowners and way too many professionals realize. The definition of an artisan, on the other hand, is someone who pays attention to such things!)

Construction Versus Design Integrity

But that doesn’t mean everything of the original construction was worthy of celebration! If integrity of original design is the standard by which to measure a house’s architectural value, one sometimes has to make a distinction between the deepest intent of the design and the actual construction of the structure.2

Take this dining room, for instance. The style of those fake panels is definitely not in character with bungalow design! Reminiscent of the classical age, they have become so ubiquitous as to have lost any distinctive reference, other than turn-of-the century “gussied up” design. “Gussied up” means “to dress or decorate in a showy way.” Like when false pillars are pretentiously pasted onto the entranceway of a modest ranch-style house in an attempt to become something it is not.

I’m not fond of the paint color, either. It would be okay for a period house in the Miami Beach Art Deco district, but it isn’t fitting for a 1923 Chicago brick bungalow. (See “Articulate Your Architecture,” an article I wrote for West Suburban Living, to get an idea of the perspective I think is appropriate for making design choices for vintage interiors.)

This room, then, seemed the perfect place to begin my interior restoration plans. For one thing, the dimensions are reasonably modest: 12 1/2 by 13 1/2 feet with a 9 foot ceiling. And the room feels self-contained (as a dining room should…more about this in a future posting). Also, because dining and living rooms are public “show-rooms”–that is, rooms you show–they are the most important places for doing period restorations. It seems a good place, then, to flex my restoration muscles. My intent, then, is to restore this room to period condition. It is my cobbler-defies-limitations-and-attempt-to-make-his-own-shoes gesture towards doing a “whole room restoration” on one of my own rooms. (And when I’m done with the dining room, I’ll move onto the living room…the kitchen…the back porch. This cobbler needs many pairs of shoes! But first things first…)

Deconstruction Before Restoration

The first thing I did was to remove the moldings that defined the perimeter of the panel fields. Then the plaster canvas had to go.

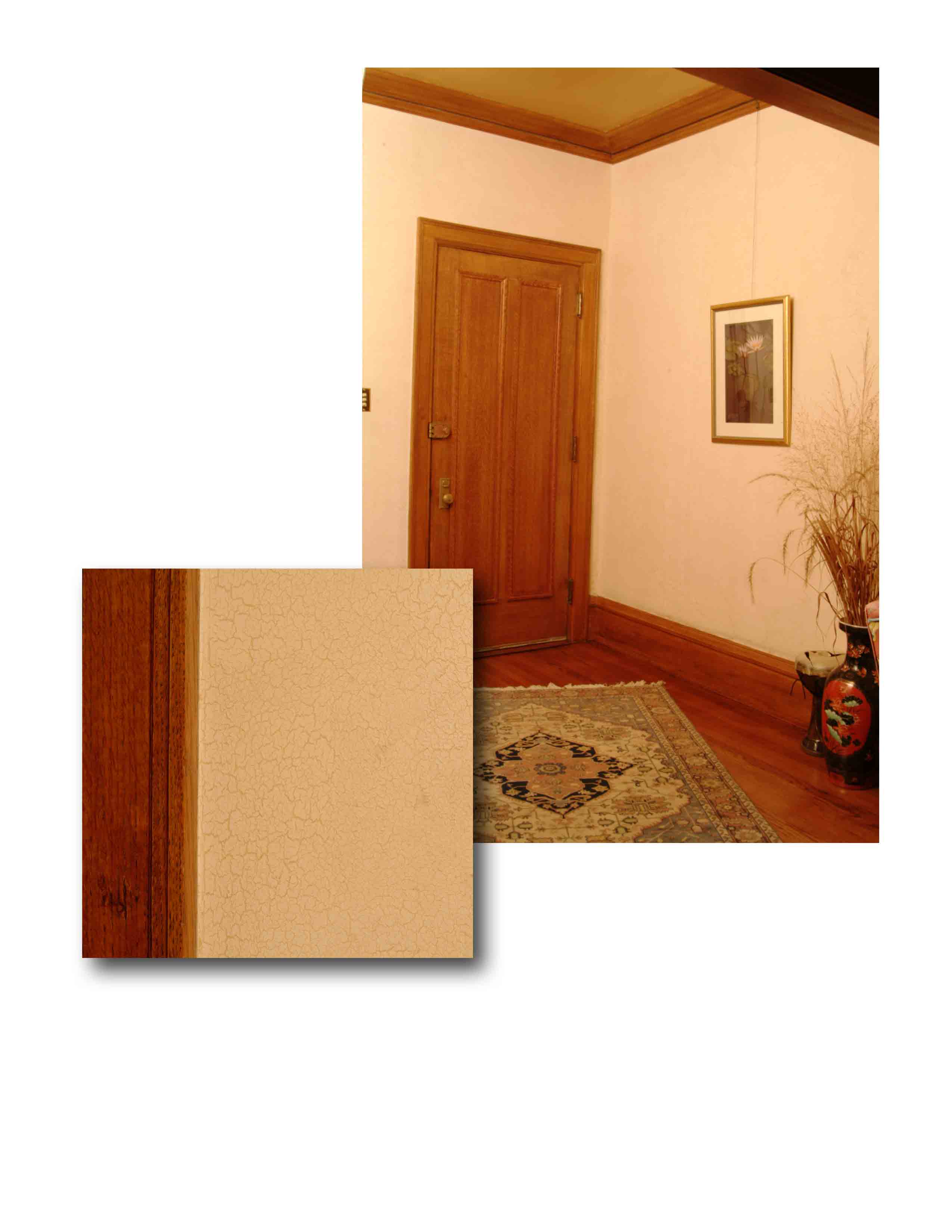

What’s a plaster canvas? Here’s a piece of it after its been removed. (You’ll notice the walls have been painted. But that story will have to be told in another post. And there IS a story to be told.)  Plaster canvas is a cloth-mesh material that is something akin to thick wallpaper. Back in the day when walls were made of plaster, new walls were routinely lined with this canvas. The intent was that the canvas liner would hide the inevitable cracks that would eventually show up in the plaster walls. (Imagine such thoughtfulness being done in contemporary construction! Thoughtfulness, by the way (IMO), is the essence of craftsmanship.)

Plaster canvas is a cloth-mesh material that is something akin to thick wallpaper. Back in the day when walls were made of plaster, new walls were routinely lined with this canvas. The intent was that the canvas liner would hide the inevitable cracks that would eventually show up in the plaster walls. (Imagine such thoughtfulness being done in contemporary construction! Thoughtfulness, by the way (IMO), is the essence of craftsmanship.)

Like a lot of things in life, plaster canvas liners are a good idea until they are no longer a good idea. Once they begin to fail, they become a liability. Old liners tend to separate from the corners first, often causing unsightly wrinkled and/or rounded-over corners. And where moisture has soaked through the wall, the liner can delaminate, leaving a small pocket of loose material in the middle of a wall. After many layers of paint have been applied over them, they begin to crackle. In my case, though, matters were even worse.

Whoever installed the liner in my dining and living rooms had failed to properly seal the walls before hanging the canvas. (It is not always the case, I have learned, that the “old timer” craftsmen always did good work!) This meant the glue that was supposed to attach the canvas to the wall had partially soaked into the plaster, resulting in a weak bond between the canvas and the wall. The effect this had on the liner was to eventually cause it to crackle like the example in this picture shows. (The cracks are easier to see if you click on the photo to view a larger image. A photographer, though, I am not.)

Now a crackle finish is fine if that is the effect you are after, as it was when we rendered it on the walls of this foyer.

But I didn’t want a crackled finish on these walls. So I pulled it down. And since it had been improperly installed, it was almost as easy to peel as a banana.3

But since the walls had not been properly sealed, removing the adhesive from the walls was a whole different story. The adhesive had soaked into the plaster. It wasn’t coming off with any kind of removal liquid remover we tried on it. We ended up having to sand it off with a palm sander. Even with the precautions of connecting the palm sander to a shop vac and sealing off the room, the dust went everywhere.

Another task one should prepare oneself for when venturing to remove degraded plaster canvas is a lot of plaster repair. One can pretty much count on having to rebuild most or all of the corners. And, depending upon the stability of the house’s foundation and structural integrity, the walls may have many cracks. Where there has been moisture damage, there may also be crumbling plaster, sometimes all the way back to the lathe board.

But that is the thing about these vintage structures. They were built in the midst of “repair culture.” That is to say, they were meant to be repaired. Now we live in “replacement culture.” As I say to clients when I talk about restoration or replacement of windows, “You can either restore them so they’ll last another hundred years, or you can purchase a subscription to the replacement window industry and count on replacing your windows every five to thirty years, depending on the quality of the product.

But I shouldn’t conclude this discussion without admitting to my own folly. I was foolish enough to undertake this first project of canvas liner removal, plaster repair, and preliminary painting just two weeks prior to hosting a family gathering of 25 people. But hey, everyone needs drama in their lives, don”t they? How else would I ever get anything done if I didn’t box myself in? Wisdom is over-rated. There’s something to be said for a little folly to spice up your life!

Footnotes

1 They DID remove original doors. But they did what the preservation community advises concerning original materials of distinctive character and quality that are removed. They stored them in the basement. Of course, this isn’t the wisest practice, but it is better than throwing them out. The recommended practice is as follows: first, clearly mark the removed item with as much descriptive material as would be useful to someone wanting to restore the original structure; second, store the item in the attic (which is drier than a basement) and stack it in a way that air can circulate around the entire structure. And this practice is based on an even more fundamental principle of preservation/restoration: Do not do anything to a vintage structure that is not reversible. Fads come and go. Vintage structures, if respected (hence, properly maintained) endure.

2 Then, of course, one has to determine what kind of restoration or preservation standard applies. If the goal is exacting historic restoration and/or preservation, discrepancies between construction and original design intent might not be acceptable. But I don’t think museum-standards should apply to most residential buildings. Yet it depends on the client’s preference. In this case, I am my own client. The guideline I adopt for my own living space is to balance restoration values, personal preference, and liveability.

3 In my case, given that the liner had been improperly installed in the first place, the whole liner had to come off. This is not the case, though, in all instances where the liner has degraded. If the bulk of the liner is in good shape, but there are sections (like corners) that have degraded, the bad parts of the liner can be cut away with a utility knife so that the plaster can then be repaired and skim coats applied to restore an even surface where the liner had been cut away.

Leave a Reply